The Dutch government has taken a significant step to protect our waterways: seagoing vessels will soon be prohibited from discharging scrubber wastewater into Dutch ports and inland waters (Schuttevaer, 2025). This move, announced by Infrastructure and Water Management Minister Barry Madlener this week, especially targets the use of open loop scrubbers — systems that use seawater to strip sulfur from ship exhaust and then discharge that polluted water back into the sea.

“This groundbreaking national regulation is a major step forward as the Netherlands joins a small but bold group of countries saying: enough. Toxic scrubber wastewater has no place in our rivers or ports – it endangers our health, our ecosystems, our biodiversity, and the drinking water millions of people rely on. The Netherlands is taking action and that deserves to be celebrated as we push to end pollution in all Dutch waters.” — Tanner Tuttle, Co-executive Director, One Planet Port.

At One Planet Port, we strongly support this decision. Preventing the discharge of scrubber water helps protect human health, river systems, and overall water quality, while also safeguarding the marine environment. This action ensures that our port areas remain safe and sustainable for people, wildlife, and future generations.

What Are Scrubbers, and Why Were They Invented?

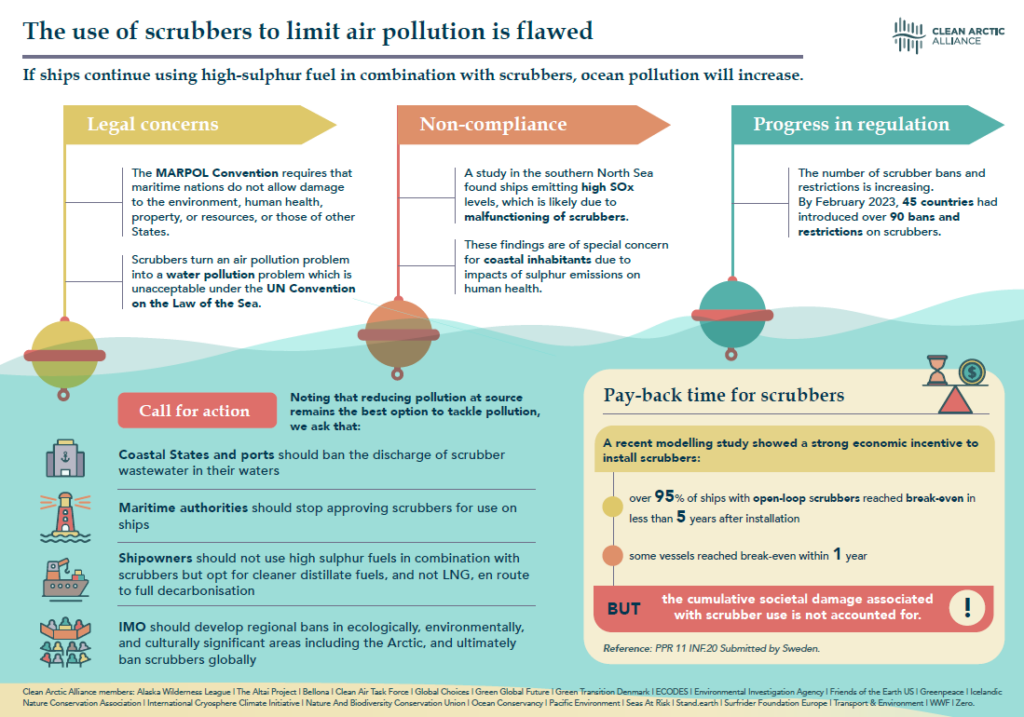

To meet the sulfur emission limits set by Regulation 14 of Annex VI of MARPOL, which came into force in 2020, the fuel industry deliberately developed scrubbers as an alternative compliance method. Annex VI permits the use of such alternatives to achieve regulatory standards, and it is this provision that enabled the widespread adoption of scrubbers instead of requiring ships to switch to cleaner fuels. Scrubbers allow ships to continue using high-sulfur fuel oil while still complying with the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) regulations aimed at significantly reducing sulfur oxide (SOₓ) emissions — pollutants known to cause acid rain and respiratory issues in humans (IMO, 2020).

Seen largely as a stopgap measure, scrubbers offered a way to comply with these environmental regulations, particularly the IMO 2020 sulfur cap, without requiring an immediate transition to cleaner but more costly fuels.

To comply, ships had two options:

-

- Switch to low-sulfur fuel (which is cleaner but more expensive), or

-

- Install exhaust gas ‘cleaning’ systems, known as scrubbers, that allow continued use of heavy fuel oil by “scrubbing” out the sulfur and transferring air pollution to water pollution.

The Problem with Open Loop Scrubbers

There are different types of scrubbers, but open loop systems are by far the most common. These systems use seawater to transform the exhaust pollution, and then discharge the resulting contaminated water — scrubber wastewater — back into the sea. This effectively shifts sulfur pollution from the air into the marine environment, where it poses serious risks to water quality and ecosystem health.

Globally, around 80% of ships equipped with scrubbers use open loop systems (British Ports Association, 2024). Not all ships have scrubbers — many use low-sulfur fuel instead — but an estimated 13% of global cargo ships—accounting for nearly 29% of total cargo fleet capacity— have opted for open loop scrubbers due to their lower operating cost.

The problem? The wastewater discharged contains toxic substances, including:

-

- Heavy metals like lead, mercury, and nickel – toxic even at low concentrations, these substances can accumulate in marine organisms and move up the food chain, ultimately affecting human health.

-

- Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) – known carcinogens and pollutants from unburned fuel residues.

-

- Acidifying components – these can lower the pH of local waters, which harms sensitive ecosystems.

In short, ships are ‘cleaning’ their air emissions, but in doing so, they are discharging an estimated 10 billion tons of contaminated wastewater into our oceans and rivers each year—polluting our water instead (ICCT, 2021).

Moreover, when comparing heavy fuel oil (HFO) with scrubbers to marine gas oil (MGO) which do not require scrubbers, research demonstrates significant increases in several key pollutants when using fuel requiring scrubbers: direct carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are 4% higher, particulate matter emissions are nearly 70% higher, and black carbon emissions are 81% higher in medium-speed diesel engines when using HFO with scrubbers (Comer et al., 2020). These findings highlight that while scrubbers enable continued use of cheaper, higher-polluting heavy fuel oil, they do not achieve equivalent emission reductions compared to directly using cleaner, low-sulfur marine gas oil.

Where Can Ships Still Dump Scrubber Wastewater?

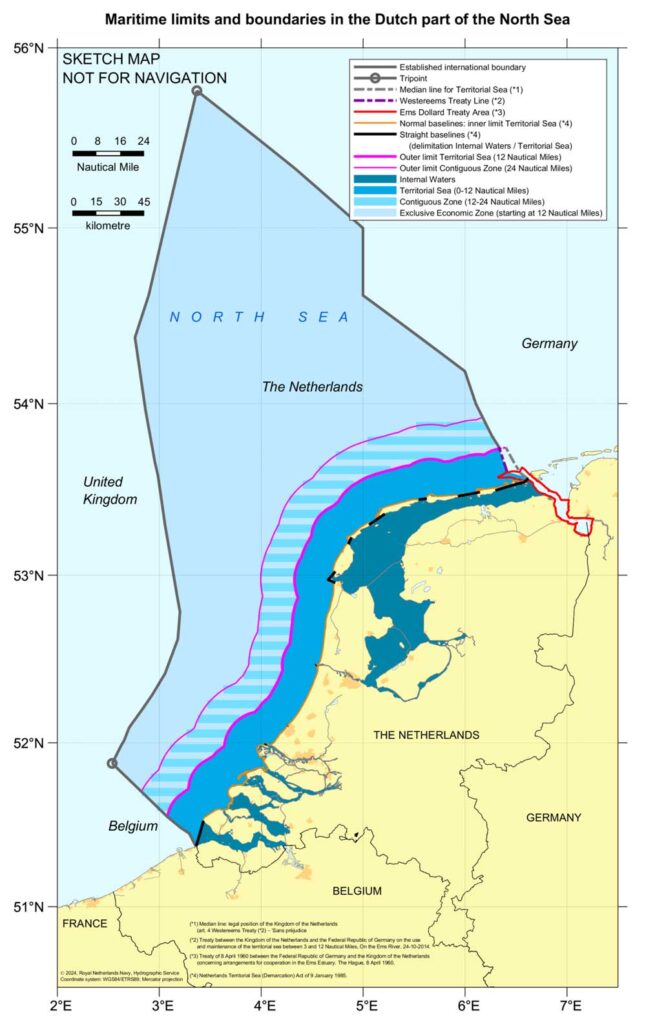

The upcoming Dutch ban only applies to ports and inland waterways. Ships can still discharge scrubber wastewater in Dutch coastal areas and open seas, including:

-

- Beyond port boundaries, unless restricted by local rules (e.g., Amsterdam already banned open loop scrubber discharges for ships at berth, from January 1, 2025).

-

- Areas beyond 12 nautical miles from shore, unless broader regional rules are adopted.

This leaves large areas of Dutch coastal waters between the port boundaries and the 12 nautical mile line—an estimated 13,000 square kilometers—still vulnerable to open-loop scrubber discharge. This area is equivalent to approximately 31% of the Netherlands’ total land surface area, highlighting the significant extent of the coastal zone still exposed to scrubber pollution. These are ecologically sensitive zones where shipping density is high and marine life is at greater risk from exposure to wastewater pollutants.

That may soon change: the Netherlands must take a position in the April 2025 meeting of the OSPAR (Oslo and Paris Commission) Environmental Impacts of Human Activities (EIHA) committee on a proposal to ban scrubber discharges within 12 nautical miles of the coast. One Planet Port, a member of Seas at Risk, supports the proposed ban, with further detail contained in a letter to the OSPAR Secretariat. If the ban was adopted, this would effectively make the full 13,000 square kilometers of Dutch coastal waters off-limits to scrubber discharge, closing the current regulatory gap and offering much broader protection for marine ecosystems. Several neighboring countries support this proposal, including Belgium, France, and Germany, and we urge the Netherlands to follow suit.

Scrubber wastewater contains toxic substances. There are no safe places to discharge it and therefore this temporary ‘clean’ stopgap for heavy fuel needs to stop.

A Local Ban with Global Implications

Critics of the Dutch ban, including the Royal Association of Netherlands Shipowners (KVNR), argue that action should be taken at the international level through the IMO. But Minister Madlener rightly notes that progress there is slow. If these critics seek global uniformity, they could just as well campaign to have the Dutch regulation adopted internationally through the IMO. In the meantime, local and national action is necessary to protect water quality and reduce pollution at the source.

The Port of Rotterdam Authority has expressed concerns about increased demand for onshore wastewater treatment infrastructure. These facilities, while already present at many large ports, are often designed for typical ship waste and stormwater, not for the volume and toxicity of scrubber wastewater. In many cases, treatment plants will need upgrading or expansion to handle this influx. While Europe has some of the highest coverage of wastewater treatment infrastructure globally, capacity and compatibility vary widely across ports. This is a valid operational challenge — but one that can be solved through investment and innovation. In fact, meeting this challenge presents an opportunity: upgrading port treatment infrastructure can create skilled green jobs, stimulate local economies, and modernize essential port services in alignment with environmental goals. We cannot let logistics delay environmental progress.

Scrubber wastewater is toxic waste. Banning its discharge into the river delta is a clear, practical move toward a cleaner, safer port.

What Needs to Happen Next

The Netherlands’ ban on scrubber discharge is a model of evidence-based policy. But for lasting change, a broader set of reforms is needed:

-

- A global ban on open-loop scrubbers through the International Maritime Organization (IMO)

-

- Transparency requirements for scrubber use and discharge volumes

-

- Support for ports to electrify infrastructure and offer shore power

-

- A just transition fund for shipping companies to invest in cleaner technologies

It is also critical to recognize that this is not just a national issue. Washwater from ships doesn’t respect borders. To truly protect our oceans, we need coordinated regional and international action.

Learn More

For more on the scrubber issue, see:

To stay informed or join our campaign for cleaner shipping, subscribe (bottom of page) to One Planet Port updates or check out our citizen science pollution monitoring program.

One Planet Port is a member of Seas at Risk and Transport & Environment (T&E).