Authored by Tanner Tuttle, MSc. (One Planet Port).

Summary

The irony is stark: the Netherlands is hailed as a global agricultural and trade powerhouse, yet its model erodes its own ecological integrity and entrenches extractive, profit-driven dynamics that harm farmers and food sovereignty worldwide. Polycrises of sea-level rise, water stress, nitrogen and biodiversity breakdown, grid and housing strain, and health harms demand a shift to sufficiency: govern material flows, phase out fossil fuels and PFAS, and prioritize well-being within planetary boundaries.

1. Introduction: Why the Netherlands Matters Now

The Netherlands, a small but hyper-globalized nation, is more than a key node in global trade; it is a harbinger of systemic collapse or transformation. With the Port of Rotterdam as Europe’s largest port1 and one of the world’s largest oil and chemical hubs, a globally connected airport (Schiphol), and the status of second-largest agricultural exporter in 2022 by value globally2, the country has achieved outsized economic influence relative to its size. However, this model is cracking under its own weight3.

Historically enriched through colonial extraction and trade, the Netherlands has long relied on extracting flows of goods, people, energy, and capital4, often without accounting for their environmental or social costs5,6. For several decades, the Netherlands has faced a series of interlocking crises: ecological overshoot7, e.g., emitting more pollution than the Dutch land can absorb or regenerate8, and resource conflicts9. This translates to tensions between farmers and the government over nitrogen emissions policy, and infrastructure congestion (e.g., Dutch electricity grid is overloaded10), which has fueled intensifying political polarization11. In this context, the Netherlands is a canary in the coal mine: its vulnerabilities are warnings for the world. With one of the world’s highest material footprints and net imports of resources, the Netherlands illustrates the structural limits of an extractivist global economy. Its pressures are not an isolated national failure but a warning of the risks inherent in the system itself.

2. From Historical Extractor to Systemic Risk

The Netherlands’ economic model is the product of centuries of extractive trade12. From the seventeenth-century founding of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), which dominated global spice routes13,14, to today’s fossil-fuel15 and agri-logistics hubs, the Dutch economy has prospered by externalizing ecological and human costs to other regions5. It has built its wealth by importing raw materials, whether colonial goods, fossil fuels, or agricultural feedstocks, and exporting finished products, chemicals, refined fuels, and food6.

A striking example: in 2017 the Netherlands was the second-largest exporter of agricultural products in the world (by value), behind only the United States16, despite occupying only about 0.4% of the land area of the continental United States. This feat relies on massive inputs of imported fertilizers17–25, animal feed26, and fossil fuels17,27–32. Dutch agriculture is hyper-intensive and technologically advanced, with yields that are among the highest in the world, for example, greenhouse tomato yields can exceed 500 tonnes per hectare annually33, more than ten times the global average34. Yet such productivity is only possible through an energy- and input-addicted system that is heavily industrialized and ecologically costly, driving soil degradation, water pollution, and biodiversity loss35,36.

In short, the Netherlands exports food but imports the energy15 and raw material37 burdens that make those exports possible. This system depends on unequal exchanges: soy for livestock feed linked to deforestation in South America38–41 and fertilizers drawn from geopolitically fragile supply chains42,43. Dutch agriculture relies on natural-gas-based nitrogen fertilizers44 increasingly tied to imported LNG from U.S. fracking45, making it vulnerable to energy price, and geopolitical, shocks46,47 and environmental injustices borne by frontline communities abroad48,49. Potash from Russia and Belarus50 and phosphate from Morocco and Western Sahara51,52 further expose the sector to geopolitical risks and unresolved questions of sovereignty and consent. These dependencies reveal a paradox: practices deemed too harmful within the EU, such as fracking, are outsourced abroad45, reproducing colonial continuities in global resource flows53.

Now, this model itself is threatening its own people and its own ecosystem. Much of the country lies below sea level and is at severe risk from sea level rise. Approximately 26% of the Netherlands’ territory is below mean sea level, and about 60% is vulnerable to floods from the North Sea, rivers, or lakes54 as sea level rise intensifies due to climate change. Crucially, the regions most at risk for floods are also the country’s centers of economic activity, including the Randstad (Amsterdam–Rotterdam–The Hague–Utrecht), Rotterdam port, and Schiphol airport55–62.

At the same time, the Netherlands faces growing drought and drinking-water stress: the RIVM has warned that by 2030 the country as a whole could face water shortages63,64 if no urgent action is taken, even as vast amounts of freshwater continue to be consumed by intensive livestock and agricultural production65. According to the European Environment Agency’s climate risk assessment, these converging pressures, flooding, drought, and heat stress, are set to intensify across Europe, with the Netherlands standing out as a high-exposure case66.

To arrest further sea-level rise, and to reduce the converging pressures of drought and heat stress, the underlying driver, global warming, must be stopped. Analyses indicate that stabilizing the climate would require the removal or neutralization of on the order of 10–20 gigatonnes of CO₂ per year this century67,68. Such numbers illustrate the sheer scale of the problem: no plausible portfolio of technological carbon removal can achieve this alone. The only realistic pathway is to drastically reduce the activities generating CO₂e in the first place, giving ecosystems space to absorb carbon naturally. Yet the Netherlands continues to operate as a high-emission (direct and indirect) trade and logistics hub via the materials flows69,70 that it facilitates, intensifying the very climate risks to which it is most exposed.

3. Crisis Convergence: Vulnerabilities in the Dutch System

The Netherlands is facing a polycrisis, a convergence of economic, ecological, and social pressure points that reveal the fragility of its model:

- General well-being: Alongside material pressures, the polycrisis erodes social cohesion. Rising rates of mental health problems, loneliness, and social isolation reflect the atomisation of society, which climate disruption and economic insecurity are likely to worsen further.

- Sea level rise: With much of its land below sea level, the country is directly at risk from climate change driven sea level rise, even as it maintains dependence on fossil-fueled trade.

- Housing crisis: Skyrocketing prices and shortages reflect space scarcity, speculative investment, and the financialization of housing. These dynamics deepen social fragmentation: while some households are forced into shared or subdivided dwellings, others consolidate properties or expand in high-value urban cores, reinforcing unequal access to living space71.

- Energy and grid crisis: Renewable energy production is growing, particularly solar and wind, but the national electricity grid lacks sufficient capacity to transport and store this energy reliably. As a result, businesses and solar producers face delays in connection or forced curtailments, resulting in inefficient use of resources and loss of revenue. Meanwhile, fossil fuel infrastructure72 still dominates large portions of the energy mix, slowing the shift toward cleaner systems73.

- Public health & environmental health degradation: Schiphol airport, the Rotterdam port, industrial agriculture, and chemical production facilities such as Chemours are major sources of air74, noise75, soil, and water pollution35, affecting the health of local communities. For example, breathing the air in Rotterdam has been compared to passively smoking almost seven cigarettes per day76. Affecting air, water, and soil, the PFAS contamination crisis illustrates the toxic health risks facing Dutch communities: RIVM has warned that eggs from free-range hobby farmers near Dordrecht contain PFAS concentrations so high they are unsafe for human consumption77, with long-term exposure linked to cancer, immune suppression, and developmental harm. Meanwhile, the healthcare system is under growing strain: significant staff shortages are projected in the coming decade78–81 with evidence of rapidly rising healthcare costs82,83.

- Public vs. corporate (and geopolitical) power: Citizens call for reduced flights84, fewer cruise ships85, and an end to fossil subsidies86. Yet corporate lobbies and foreign governments exert outsized influence to protect entrenched interests, most strikingly when the Dutch government attempted to reduce flight numbers at Schiphol, only for the plan to be blocked under pressure from the United States87 and the EU87,88.

- Ecological breakdown: Soil depletion, nitrogen pollution89, biodiversity collapse90, and water contamination reflect an economy that has prioritized throughput over sufficiency.

- Demographic strain: The Netherlands is experiencing a complex demographic situation involving natural population decline while maintaining overall population growth through labor immigration91, e.g., to funnel workers to sectors such as agriculture and the meat industry, even in the face of covid and the Russia-Ukraine war.

- Institutional and political crisis: The Netherlands’ political landscape over the past decades has been marked by an institutional inability to respond coherently to converging crises. The past three cabinets have all collapsed prematurely, reflecting a governmental crisis that has deepened public mistrust in institutions. In this vacuum, populist narratives have surged, with refugees and immigrants frequently scapegoated for housing shortages and pressure on social services. Racist sentiments are rising, despite evidence that 1 in 10 people in the Netherlands reported feeling discriminated against in 202392, and critical scholarship highlights how Dutch society has often struggled to confront structural racism93.

While many Western economies externalize ecological costs in similar ways, the Dutch economic model is distinctive in its intensity and exposure. The Netherlands’ extreme spatial density, global trade centrality, and legal constraints arising from excess nitrogen pollution94 make the costs of extractivism unusually visible and acute.

This economic model imposes enormous costs on Dutch society. Individual health expenditures already amount to 10.2% of GDP95, while environmental damage accounts for another 5.8%96, and fossil fuel subsidies remain high at an estimated 7%97 of GDP. Excess nitrogen pollution has triggered legal restrictions that stall new housing and industrial development, generating real-estate value losses and delaying urgently needed investment94,98–101. Flood risks are beginning to affect property prices, Dutch homes in flood-prone areas sell on average for 2.2-4.7% less than comparable properties102,103, echoing international projections of climate-driven value declines of 10–40% in places like California and Florida104. Additional burdens stem from publicly funded infrastructure repairs and society-financed tax and regulatory breaks for ecologically harmful sectors, including shipping subsidies (0.7% of GDP105,106), aviation tax exemptions (0.25% of GDP107).

On conservative assumptions, these costs amount to a significant portion of GDP being tied up, much of it sustaining activities with short-lived benefits and persistent ecological harms. Beyond these measurable costs, further environmental harm erodes the country’s ecological and economic resilience (e.g., polluting of soils, air, and water), while delaying investment in regenerative and equitable alternatives.

These overlapping crises are symptoms of a deeper truth: the Dutch economic model has reached its limits. Yet in this convergence lies an opportunity. By acknowledging the interconnected nature of its vulnerabilities, the Netherlands can also recognize the potential for systemic renewal. The breakdown of the old model opens space for a new one, an economy designed to deliver sufficiency, resilience, and shared prosperity within planetary boundaries, i.e., ecological limits.

4. A One Planet Perspective: Why It Starts Here

As the Dutch economic model is so resource-intensive and externally dependent, it cannot endure within planetary limits. Yet this very intensity makes the Netherlands the ideal testbed for transformation: if a highly globalized, trade-driven nation can shift toward sufficiency, others can follow.

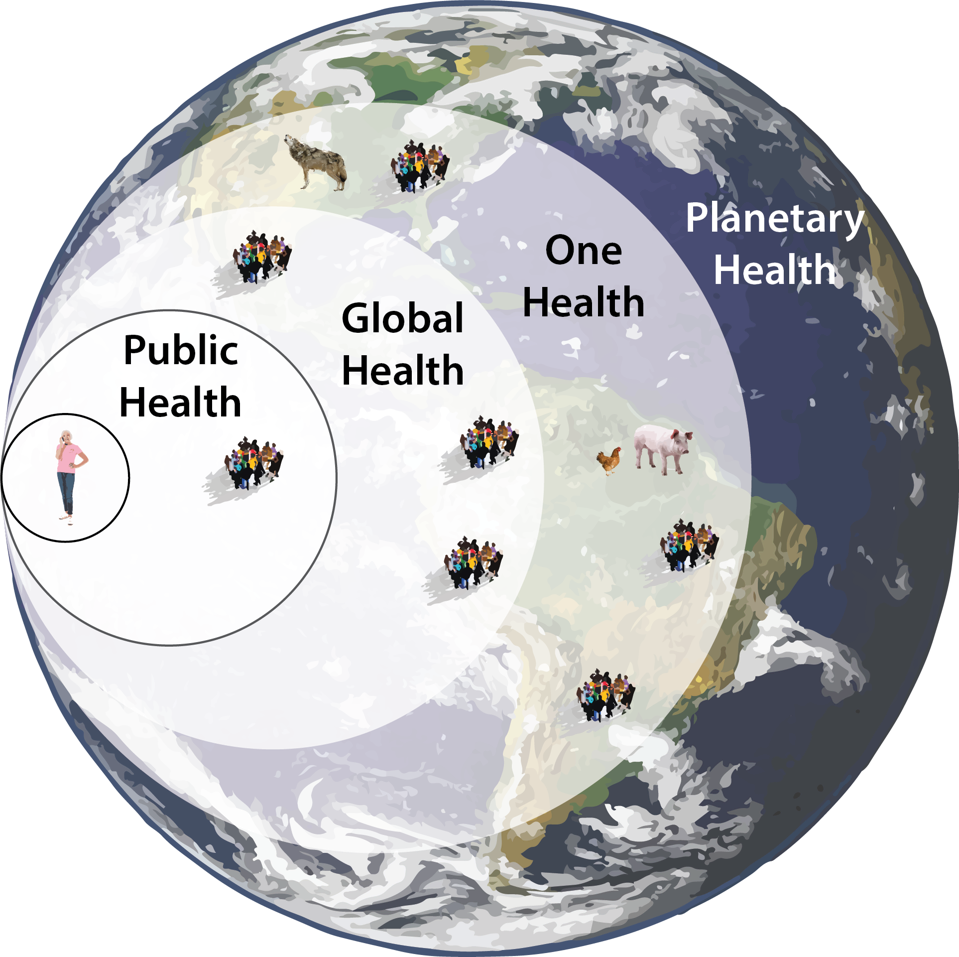

A “One Planet” system, including economy, recognizes ecological boundaries while securing well-being. It reframes prosperity around sufficiency rather than surplus, drawing on frameworks such as the Nine Planetary Boundaries, Doughnut Economics, One Health One Planet, and the Safe and Just Earth System Boundaries. Practical guidance is already emerging, for example through the Seas At Risk One Planet Shipping report108, which shows how global trade can be reoriented toward sustainability.

Image credit: Global Health Matters

The Dutch legacy makes the case plain. The VOC pioneered shareholder capitalism and financialized trade; today that same model destabilizes ecology and society. If the Netherlands helped design extractivist capitalism, it can also pioneer its reinvention109–112, shifting from shareholder profit to shared well-being, from GDP growth to indicators of resilience, justice, and ecological integrity.

With cutting-edge research institutions, organized civil society, and high spatial awareness, the Netherlands has the tools, the knowledge, and the human capacity to lead this change. What is required is political will. By choosing sufficiency and regeneration over an extractive dead end, the Netherlands can become a luminous example of systemic renewal, proving that a thriving future within planetary limits is both possible and achievable.

5. Conclusion: Collapse or Co-Creation

The Netherlands is no longer merely a case study in modern trade efficiency, it is a litmus test for human and planetary well-being. It has reached the limits of a system premised on infinite growth, planetary disregard, and extractive flows. A deeper synthesis of its challenges, to build a definitive stepwise transition plan, is not only useful, it is essential for its survival.

The stakes are global. But the transformations are local. A One Planet Netherlands would mean establishing a national observatory for material flows, tracking in vivid detail imports, exports, and embodied emissions so society can govern what passes through Rotterdam and beyond. It would mean clear phase-out commitments: a timetable to end fossil fuels, halt fossil hydrogen projects, and eliminate PFAS in industrial production. And it would mean targeted innovation, such as a clean industrial cluster to replace toxic products like HFCs with sustainable alternatives, made commercially viable and regionally scalable. These are not distant ideals: pilots are already underway in Rotterdam, Dutch cities are experimenting with circular economy zones, and citizen cooperatives are generating clean energy for their neighborhoods.

Whether the coming transformation is chaotic and imposed, or intentional and co-created, depends on what happens now. The upcoming Dutch elections represent a pivotal opportunity to chart a new course, one rooted in ecological responsibility, shared prosperity, and democratic renewal. Will the Netherlands choose to lead a guided transition, setting an example of post-extractive, One Planet living, or will it be overtaken by the collapse of the very systems it helped to build?

At the One Planet Port foundation, we are building communities of courage, collaboration, and care, starting from our base in Rotterdam, the epicenter of both risk and possibility. Join us in advancing a vision, and stepwise plan, where prosperity comes from sufficiency and regeneration rather than extraction: ports that enable clean trade, farms that nourish ecosystems, clean energy that strengthens communities, and mobility systems that connect people without polluting the future. This is our moment to choose life over extraction, solidarity over fragmentation, and to proudly stand with Team Human113, amplifying human connection, resisting dehumanizing pressures of technologies, markets, and institutions, and reclaiming cooperative, human-centered ways of organizing.

References

1. Bunkermarket. Rotterdam’s 2024 Bunker Sales Records 9.8M Tonnes, LNG Growth Soars. (2025).

2. Reiley, L. Cutting-edge tech made this tiny country a major exporter of food. The Washington Post (2022).

3. Kuper, S. The Netherlands may be the first country to hit the limits of growth. FT (2022).

4. Bosma, U. The economic historiography of the dutch colonial empire. Tijdschr. Soc. Econ. Geschied./ Low Ctries. J. Soc. Econ. Hist. 11, 153 (2014).

5. Ecological footprint of Dutch consumption, 2005. Compendium voor de Leefomgeving https://www.clo.nl/en/indicators/en007506-ecological-footprint-of-dutch-consumption-2005.

6. Aerts, N. & Weijers, S. Use of imports in the Dutch economy – Dutch Trade in Facts and Figures, 2023. Use of imports in the Dutch economy – Dutch Trade in Facts and Figures, 2023 | CBS https://longreads.cbs.nl/dutch-trade-in-facts-and-figures-2023/use-of-imports-in-the-dutch-economy.

7. Global Footprint Network. The Netherlands Fact Sheet. Global Footprint Network https://www.footprintnetwork.org/netherlands/ (2022).

8. Claessens, J. et al. Agricultural Practices and Water Quality in the Netherlands: Status (2020–2023) and Trends (1992–2023). https://www.rivm.nl/publicaties/agricultural-practices-and-water-quality-in-netherlands-status-2020-2023-and-trends.

9. Tullis, P. Nitrogen wars: the Dutch farmers’ revolt that turned a nation upside-down. The Guardian (2023).

10. The Grid Congestion Problem: “Policy makers could have scratched their heads a little sooner.” Hanze Hogeschool Groningen https://www.hanze.nl/en/news/hanze-news/2024/05/the-grid-congestion-problem-policy-makers-could-have-scratched-their-heads-a-little-sooner.

11. Netherlands: Freedom in the World 2023 Country Report. https://freedomhouse.org/country/netherlands/freedom-world/2023 (2023).

12. de Zwart, P. Globalization in the early modern era: New evidence from the Dutch-Asiatic trade, c. 1600–1800. J. Econ. Hist. 76, 520–558 (2016).

13. Gaastra, F. S. The Dutch East India Company: expansion and decline : Gaastra, F.S.: Amazon.nl: Books. https://www.amazon.nl/Dutch-East-India-Company-expansion/dp/9057302411 (2003).

14. Parthesius, R. Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters: The Development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Shipping Network in Asia 1595-1660. (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2010). doi:10.5117/9789053565179.

15. Netherlands: energy dependency rate 2008-2020. Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/267651/dependency-on-energy-imports-in-the-netherlands/ (2022).

16. Whiting, K. These Dutch tomatoes can teach the world about sustainable agriculture. World Economic Forum https://www.weforum.org/stories/2019/11/netherlands-dutch-farming-agriculture-sustainable/ (2019).

17. No change in natural gas consumption in 2024. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2025/07/no-change-in-natural-gas-consumption-in-2024 (2025).

18. Garske, B., Heyl, K. & Ekardt, F. The EU Communication on ensuring availability and affordability of fertilisers—a milestone for sustainable nutrient management or a missed opportunity? Environ. Sci. Eur. 36, 1–5 (2024).

19. European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Ensuring Availability and Affordability of Fertilisers. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52022DC0590(01) (2022).

20. European Commission. Agri-environmental indicator – mineral fertiliser consumption. Eurostat Statistics Explained https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Agri-environmental_indicator_-_mineral_fertiliser_consumption (2024).

21. Industry Facts and Figures 2023. https://www.fertilizerseurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Industry-Facts-and-figures-2023.pdf (2023).

22. TheGlobalEconomy.com. Netherlands: Fertilizer use. TheGlobalEconomy.com https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Netherlands/fertilizer_use/ (2022).

23. TradingEconomics.com. Netherlands: Fertilizer consumption (% of fertilizer production). Netherlands: Fertilizer consumption (% of fertilizer production) https://tradingeconomics.com/netherlands/fertilizer-consumption-percent-of-fertilizer-production-wb-data.html.

24. Netherlands Imports: Fertilizers. TradingEconomics.com https://tradingeconomics.com/netherlands/imports/fertilizers.

25. Netherlands Imports of Fertilizer (HS Code 310290) from All Countries – 2023. World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/NLD/year/2023/tradeflow/Imports/partner/ALL/product/310290 (2023).

26. van Selm, B. et al. Recoupling livestock and feed production in the Netherlands to reduce environmental impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 899, 165540 (2023).

27. Engelke, P. & Webster, J. Rotterdam, Netherlands: An Integrated Approach to Decarbonization. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/rotterdam-netherlands-an-integrated-approach-to-decarbonization/ (2023).

28. Netherlands: Natural Gas Imports. CEIC https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/netherlands/natural-gas-imports (2018).

29. Enerdata. Netherlands Energy Market Report. Enerdata eStore https://www.enerdata.net/estore/energy-market/netherlands/ (2025).

30. IEA. Netherlands: Energy Mix. IEA.org https://www.iea.org/countries/the-netherlands/energy-mix (2025).

31. NL Times. Indirect emissions from Rotterdam port 3.5 times higher than all of Netherlands. NL Times https://nltimes.nl/2024/12/16/indirect-emissions-rotterdam-port-35-times-higher-netherlands (2024).

32. TradeImeX. EU Oil Imports – Top Importing Countries in Europe. TradeImeX Blog https://www.tradeimex.in/blogs/eu-oil-Imports (2024).

33. Ibarrola-Rivas, M.-J., Castro, A. J., Kastner, T., Nonhebel, S. & Turkelboom, F. Telecoupling through tomato trade: what consumers do not know about the tomato on their plate. Glob. Sustain. 3, e7 (2020).

34. Šalagovič, J. et al. Microclimate monitoring in commercial tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) greenhouse production and its effect on plant growth, yield and fruit quality. Front. Hortic. 3, (2024).

35. van Grinsven, H. J. M., van Eerdt, M. M., Westhoek, H. & Kruitwagen, S. Benchmarking Eco-efficiency and footprints of dutch agriculture in European context and implications for policies for climate and environment. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 3, 442712 (2019).

36. de Wolf, P., Ros, G. H. & Berkhout, P. Is something up with soil? Wageningen University & Research https://www.wur.nl/en/show-longread/is-something-up-with-soil.htm (2022).

37. Hall, L. Netherlands’ strategy for sourcing critical materials. Euro Weekly News https://euroweeklynews.com/2025/02/15/netherlands-strategy-for-sourcing-critical-materials/ (2025).

38. Villoria, N., Garrett, R., Gollnow, F. & Carlson, K. Leakage does not fully offset soy supply-chain efforts to reduce deforestation in Brazil. Nat. Commun. 13, 5476 (2022).

39. Song, X.-P. et al. Massive soybean expansion in South America since 2000 and implications for conservation. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 784–792 (2021).

40. Pendrill, F. et al. Agricultural and forestry trade drives large share of tropical deforestation emissions. Glob. Environ. Change 56, 1–10 (2019).

41. Curtis, P. G., Slay, C. M., Harris, N. L., Tyukavina, A. & Hansen, M. C. Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Science 361, 1108–1111 (2018).

42. Information Note: The importance of Ukraine and the Russian Federation for global agricultural markets and the risks associated with the current conflict. ReliefWeb https://reliefweb.int/report/world/information-note-importance-ukraine-and-russian-federation-global-agricultural-markets.

43. Paulson, N., Zulauf, C., Schnitkey, G. & Baltz, J. Fertilizer prices continue year-long decline from 2022 peak. farmdoc daily 13, (2023).

44. Decarbonisation options for the Dutch fertiliser industry. PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency https://www.pbl.nl/en/publications/decarbonisation-options-for-the-dutch-fertiliser-industry.

45. People, O. Netherlands – Fracked Gas Imports: Briefing – Food & Water Action Europe. Food & Water Action Europe https://www.foodandwatereurope.org/blogs/netherlands-fracking-briefing/ (2023).

46. Bednarski, L., Roscoe, S., Blome, C. & Schleper, M. C. Geopolitical disruptions in global supply chains: a state-of-the-art literature review. Prod. Plan. Control 1–27 (2023) doi:10.1080/09537287.2023.2286283.

47. Yang, Z., Du, X., Lu, L. & Tejeda, H. A. Price and volatility transmissions among natural gas, fertilizer, and corn markets: A revisit. J. Risk Fin. Manag. 15, 1–14 (2022).

48. McKenzie, L. M., Witter, R. Z., Newman, L. S. & Adgate, J. L. Human health risk assessment of air emissions from development of unconventional natural gas resources. Sci. Total Environ. 424, 79–87 (2012).

49. Scientists, A. Hydraulic Fracturing and Health. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/fracking.

50. Kee, J., Cardell, L. & Zereyesus, Y. A. Global Fertilizer Market Challenged by Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2023/september/global-fertilizer-market-challenged-by-russia-s-invasion-of-ukraine.

51. Allan, J. Natural resources andintifada: oil, phosphates and resistance to colonialism in Western Sahara. J. North Afr. Stud. 21, 645–666 (2016).

52. Allan, J. & Ojeda-García, R. Natural resource exploitation in Western Sahara: new research directions. J. North Afr. Stud. 27, 1107–1136 (2022).

53. Claar, S. Global energy partnerships: Green colonialism and an ecological new international economic order. in Global Partnerships and Neocolonialism 123–144 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2025). doi:10.1007/978-3-031-87005-7_6.

54. van Alphen, J., Haasnoot, M. & Diermanse, F. Uncertain accelerated sea-level rise, potential consequences, and adaptive strategies in the Netherlands. Water (Basel) 14, 1527 (2022).

55. de Moel, H., Aerts, J. C. J. H. & Koomen, E. Development of flood exposure in the Netherlands during the 20th and 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 620–627 (2011).

56. Jongman, B., Koks, E. E., Husby, T. G. & Ward, P. J. Increasing flood exposure in the Netherlands: implications for risk financing. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1245–1255 (2014).

57. Kind, J. M. Economically efficient flood protection standards for theNetherlands: Efficient flood protection standards for the Netherlands. J. Flood Risk Manag. 7, 103–117 (2014).

58. Eijgenraam, C. et al. Economically efficient standards to protect the Netherlands against flooding. Interfaces (Providence) 44, 7–21 (2014).

59. Punt, E., Monstadt, J., Frank, S. & Witte, P. Beyond the dikes: an institutional perspective on governing flood resilience at the Port of Rotterdam. Marit. Econ. Logist. 25, 230–248 (2023).

60. de Moel, H., van Vliet, M. & Aerts, J. C. J. H. Evaluating the effect of flood damage-reducing measures: a case study of the unembanked area of Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Reg. Environ. Change (2013) doi:10.1007/s10113-013-0420-z.

61. Dolman, N., Sindhamani, V. & Vorage, P. Keeping airports open in times of climatic extremes: Planning for climate-resilient airports. in The Palgrave Handbook of Climate Resilient Societies 1015–1038 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021). doi:10.1007/978-3-030-42462-6_8.

62. Kuller, M., Dolman, N. J., Vreeburg, J. H. G. & Spiller, M. Scenario analysis of rainwater harvesting and use on a large scale – assessment of runoff, storage and economic performance for the case study Amsterdam Airport Schiphol. Urban Water J. 14, 237–246 (2017).

63. Quick action needed to prevent drinking water shortage in 2030. https://www.rivm.nl/en/news/quick-action-needed-to-prevent-drinking-water-shortage-in-2030.

64. Waterbeschikbaarheid voor de bereiding van drinkwater tot 2030 – knelpunten en oplossingsrichtingen. https://www.rivm.nl/publicaties/waterbeschikbaarheid-voor-bereiding-van-drinkwater-tot-2030.

65. Watergebruik in de land- en tuinbouw, 2001-2023. Compendium voor de Leefomgeving https://www.clo.nl/indicatoren/nl001419-watergebruik-in-de-land-en-tuinbouw-2001-2023.

66. European Climate Risk Assessment. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/european-climate-risk-assessment.

67. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al. Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda. (National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., DC, 2019). doi:10.17226/25259.

68. Abouelnaga, M. Carbon Dioxide Removal: Pathways and Policy Needs. https://www.c2es.org/document/carbon-dioxide-removal-pathways-and-policy-needs/ (2021).

69. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Smaller material footprint, more recycling than the EU average. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek [Central Bureau of Statistics] https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2020/08/smaller-material-footprint-more-recycling-than-the-eu-average (2020).

70. Lemmers, O. & Wong, K. F. Distinguishing between imports for domestic use and for re-exports: A novel method illustrated for the Netherlands. Natl. Inst. Econ. Rev. 249, R59–R67 (2019).

71. Lennartz, C., Baarsma, B. & Vrieselaar, N. Exploding house prices in urban housing markets: Explanations and policy solutions for the Netherlands. in Hot Property: The Housing Market in Major Cities 207–221 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019). doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11674-3_18.

72. IEA. The Netherlands 2020: Energy Policy Review. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-netherlands-2020 (2020).

73. Pató, Z. Gridlock in the Netherlands: How to Unblock the Electricity Grid to Accelerate the Energy Transition. https://www.raponline.org/knowledge-center/gridlock-in-netherlands/ (2024).

74. Knol, A. Factsheet (NL and English) on the consequences of ultrafine dust from Schiphol for the health of local residents. https://milieudefensie.nl/actueel/factsheet-ultrafine-particles-from-schiphol-airport-health-impact.pdf (2015).

75. Franssen, E. A. M., Staatsen, B. A. M. & Lebret, E. Assessing health consequences in an environmental impact assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 22, 633–653 (2002).

76. Nederlanders roken per dag vijf sigaretten mee door vieze lucht. Universiteit Utrecht https://www.uu.nl/nieuws/nederlanders-roken-per-dag-vijf-sigaretten-mee-door-vieze-lucht.

77. RIVM adviseert geen particuliere eieren meer te eten. https://www.rivm.nl/nieuws/rivm-adviseert-geen-particuliere-eieren-meer-te-eten.

78. van Merode, F., Groot, W., van Oostveen, C. & Somers, M. The hidden reserve of nurses in the Netherlands: A spatial analysis. Nurs. Rep. 14, 1353–1369 (2024).

79. NL Times. Dutch healthcare system expected to face a shortage of 266,000 workers by 2035. NL Times https://nltimes.nl/2024/12/17/dutch-healthcare-system-expected-face-shortage-266000-workers-2035 (2024).

80. Dantuma, E. Dutch healthcare sector set to grow despite staff shortage struggles. ING Think https://think.ing.com/articles/dutch-healthcare-staffing-shortage-growth/ (2025).

81. “Everyone in healthcare realises that something has to change.” Leiden University https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/news/2023/10/everyone-in-healthcare-realises-that-something-has-to-change.

82. van Dijk, C. E., Langereis, T., Dik, J.-W. H., Hoekstra, T. & van den Berg, B. The health and long-term care costs in the last year of life in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Health Econ. 26, 1149–1162 (2025).

83. Bakx, P., O’Donnell, O. & van Doorslaer, E. Spending on Health Care in the Netherlands: Not Going So Dutch: Spending on health care in the Netherlands. Fisc. Stud. 37, 593–625 (2016).

84. Lecca, T. Dutch brawl over airport noise sets tone for rest of Europe. Politico Europe (2025).

85. Prakash, P. Amsterdam has long wanted to keep “nuisance” tourists away. First, it banned new hotels and now, it plans to ban cruises. Fortune (2024).

86. NL Times. Extinction Rebellion activists block A12 in The Hague to protest fossil fuel subsidies. NL Times (2025).

87. NL Times. Drastic Schiphol flight reduction plan halted over US, EU pressure. NL Times (2023).

88. How the Aviation Lobby Got the European Commission to Derail Dutch Flight Reduction Plans. Corporate Europe Observatory https://corporateeurope.org/en/2023/11/how-aviation-lobby-got-european-commission-derail-dutch-flight-reduction-plans.

89. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM). Nitrogen. RIVM.nl https://www.rivm.nl/en/nitrogen (2025).

90. Utrecht University. Bending the curve of biodiversity loss starts with insight into the causes. Utrecht University (www.uu.nl) https://www.uu.nl/en/achtergrond/bending-the-curve-of-biodiversity-loss-starts-with-insight-into-the-causes (2022).

91. Statistics Netherlands (CBS). Lower population growth in 2024. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS.nl) https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2025/05/lower-population-growth-in-2024 (2025).

92. Netherlands, S. 1 in 10 people felt discriminated against in 2023. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2024/50/1-in-10-people-felt-discriminated-against-in-2023 (2024).

93. Ghorashi, H. Taking racism beyond Dutch innocence. Eur. J. Women S Stud. 30, 16S–21S (2023).

94. Stokstad, E. Nitrogen crisis from jam-packed livestock operations has “paralyzed” Dutch economy. American Association for the Advancement of Science https://www.science.org/content/article/nitrogen-crisis-jam-packed-livestock-operations-has-paralyzed-dutch-economy (2021).

95. Netherlands, S. Spending on health care up by 8.1 percent in 2024. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2025/22/spending-on-health-care-up-by-8-1-percent-in-2024 (2025).

96. What’s the damage? Monetizing the environmental externalities of the Dutch economy and its supply chain. https://www.dnb.nl/en/publications/research-publications/working-paper-2021/what-s-the-damage-monetizing-the-environmental-externalities-of-the-dutch-economy-and-its-supply-chain/.

97. Fossil Fuel Subsidies. IMF https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/climate-change/energy-subsidies (2019).

98. NL Times. Nitrogen crisis prevented construction of 23,000 homes since 2019. NL Times https://nltimes.nl/2024/01/09/nitrogen-crisis-prevented-construction-23000-homes-since-2019 (2024).

99. Colliers | The Netherlands Misses out on 23,000 Homes due to Nitrogen Ruling. https://www.colliers.com/en-nl/research/nederland-mist-23000-woningen-door-stikstofuitspraak.

100. Laio. Nitrogen crisis puts a third of Dutch housing projects at stake. IO+ https://ioplus.nl/en/posts/nitrogen-crisis-puts-a-third-of-dutch-housing-projects-at-stake (2025).

101. The impact of the nitrogen problem on the Dutch logistics real estate market. https://www.savills.com/blog/article/297153/commercial-property/the-impact-of-the-nitrogen-problem-on-the-dutch-logistics-real-estate-market.aspx.

102. Stroom, M. A climate-risk adjusted housing market: introduce policy enforcing climate-risk disclosure in residential real-estate. MCRE https://maastrichtrealestate.com/blog/a-climate-risk-adjusted-housing-market-introduce-policy-enforcing-climate-risk-disclosure-in-residential-real-estate/ (2021).

103. Is flood risk already affecting house prices? ABN AMRO Bank https://www.abnamro.com/research/en/our-research/is-flood-risk-already-affecting-house-prices.

104. Gibson, K. Climate change to obliterate $1.5 trillion in U.S. home values, study finds. CBS News https://www.cbsnews.com/news/climate-change-to-obliterate-1-5-trillion-in-us-home-values-study-finds/ (2025).

105. New study estimates The Netherlands’ fossil fuel subsidies at €37.5 billion per year, despite long-standing promises to end this support. Oil Change International https://oilchange.org/news/new-study-estimates-the-netherlands-fossil-fuel-subsidies-at-e37-5-billion-per-year-despite-long-standing-promises-to-end-this-support/.

106. Netherlands: GDP by province 2022. Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/1402227/netherlands-gdp-by-province/.

107. seo amsterdam economics. Taxes in the Field of Aviation and their impact. CE Delft – EN https://cedelft.eu/publications/taxes-in-the-field-of-aviation-and-their-impact/ (2019).

108. Seas At Risk. One Planet Shipping: Navigating the Waves of Climate Change. https://seas-at-risk.org/general-news/one-planet-shipping-for-a-sustainable-future/ (2024).

109. van der Berg, A. Climate adaptation planning for resilient and sustainable cities: Perspectives from the City of Rotterdam (Netherlands) and the City of Antwerp (Belgium). Eur. J. Risk Regul. 14, 1–19 (2022).

110. Burgercollectieven aan het roer In co-creatie met de overheid naar succesvolle transities. Kennisplatform Collectieve Kracht https://collectievekracht.eu/collectievenlab/nieuws/3011264.aspx.

111. European Environment Agency (EEA). Netherlands – Circular Economy Country Profile 2024. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/circular-economy/country-profiles-on-circular-economy/circular-economy-country-profiles-2024/netherlands_2024-ce-country-profile_final.pdf (2024).

112. van der Stoep, R., ter Stege, J. & Taverne, A. Country Report Netherlands. https://www.bosch-stiftung.de/sites/default/files/documents/2024-06/Country-report-netherlands.pdf (2024).

113. Rushkoff, D. Team Human. (WW Norton, New York, NY, 2021).